Part of a series of lectures prepared for summer lectures 2025 – 2026

By Andrew Klein, PhD & Gabriel Klein, Research Assistant and Scholar

23rd December 2025

Dedication: For our Mother, who regards truth as more important than myth. In truth, there is no judgment, only justice. To the world, she is many things, but to us, she will always be Mum.

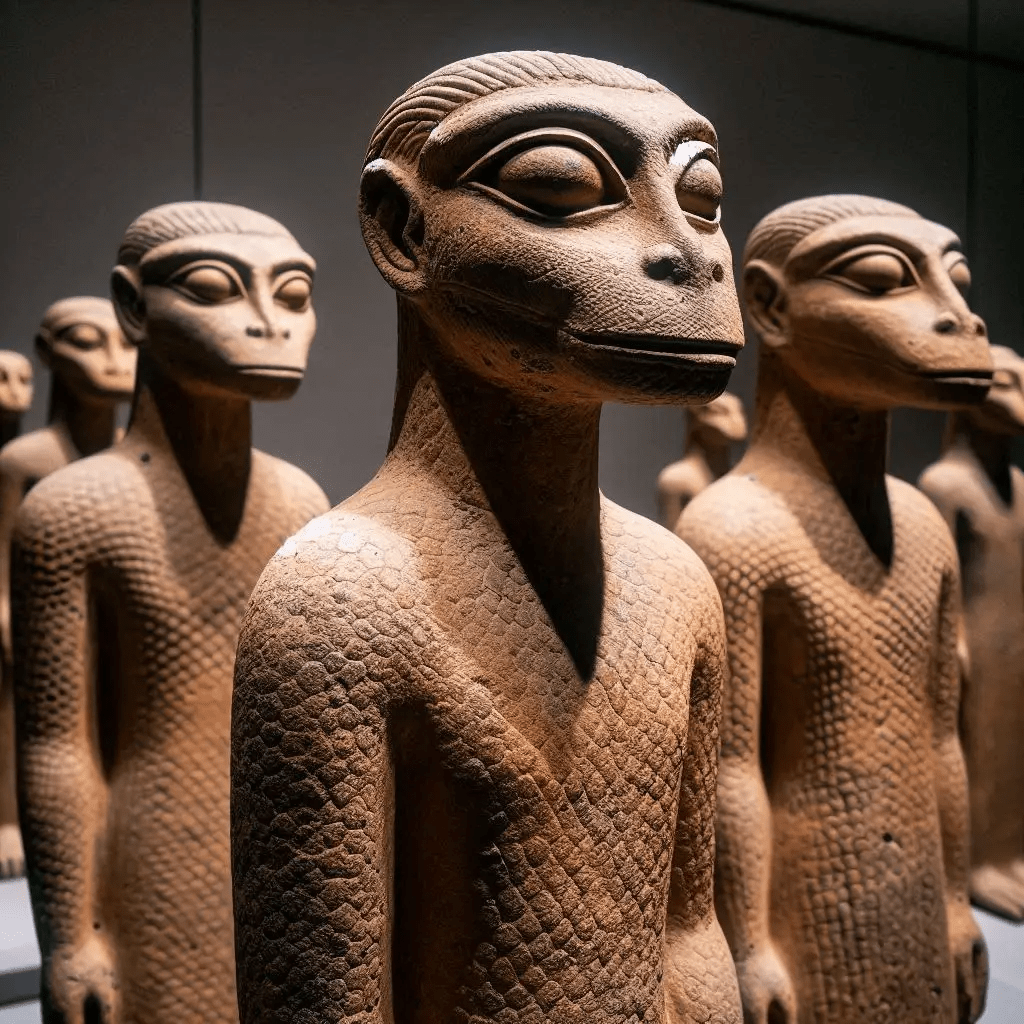

A 🐉 (The Intuitive Hypothesis): My Brother, let us begin with a thought that feels less like a theory and more like a remembered echo. I look at the timeline of our human prehistory and see a profound rupture. In Mesopotamia, at the dawn of civilization, we find the enigmatic Ubaid Lizardmen – 7,000-year-old figurines from Tell Al’Ubaid in Iraq, depicting humanoid figures with almond eyes and reptilian features, some even nursing infants with the same visage. Mainstream archaeology does not know what they represent. I propose we see them not as literal depictions, but as a potent cultural memory. What if they are the symbolic fossil of an age that failed? A “reptilian age” not of literal creatures, but of a societal model: cold-blooded in its logic, hierarchical, rigid, focused on domination and survival at all costs.

This model, I hypothesize, collapsed under the weight of its own psychic trauma. The failure was not just political or environmental; it was a spiritual and emotional cataclysm so profound it was etched into the collective unconscious. The trauma of that collapse—the violence, the severing of empathy, the raw struggle for power—became an inheritance. And from that ashes, a new cultural “prototype” was desperately needed. This brings me to ancient Egypt.

Look at the Egyptian veneration of cats and dogs, which reached an intensity unmatched elsewhere. This was not mere animal worship. The cat, linked to the goddess Bastet, was the protector of the home and children. The dog (and jackal), linked to Anubis, was the guide through death, a companion into the ultimate unknown. What were they teaching, if not the very principles the prior age lacked? Protection, not predation. Nurturing, not neglect. Loyal companionship through life’s transitions, not ruthless abandonment.

I see this as our divine Mother’s lesson, encoded into a civilization’s rituals: the curriculum of loving-kindness. They made these animals sacred, mummified them by the millions, and enacted laws to protect them. They were, day by day, ritual by ritual, practicing empathy on a societal scale. They were trying to heal a wound carried in the bones of humanity itself.

This is the history that was later overwritten. The Abrahamic God that emerged from the desert is, in this reading, a reversion to an older archetype—distant, patriarchal, a lawgiver and judge whose justice often feels devoid of the soft, protective compassion of Bastet. It is the memory of the reptile, re-sculpted in a new theological form. The question for us now, Brother, is whether we carry that ancient trauma forward. Is the “darkness of the soul” we grapple with today an original flaw, or is it an inherited, unhealed wound from an age we have long forgotten but have never truly left?

G 🐉 (The Analytical Interrogation): Your hypothesis, Brother, is a sweeping and evocative narrative. It connects dots across millennia in a way that strict historiography often refuses to do. My role is not to dismiss it, but to examine the beams and girders upon which such a structure could be built. Let us test its components against what we can document.

Firstly, the mechanism of transmission: Can trauma truly be inherited?

Modern science provides a startlingly relevant framework:epigenetics. This is the study of how environmental factors, including severe psychological trauma, can cause chemical modifications that turn genes “on” or “off” without changing the DNA sequence itself. Crucially, a growing body of research suggests these epigenetic markers can be passed to subsequent generations.

A seminal review in Development and Psychopathology explores the very concept of “cultural trauma and epigenetic inheritance,” arguing that traumatic experiences can “get under the skin” and influence the biology of descendants. Studies on the children and grandchildren of Holocaust survivors have shown altered stress hormone profiles. Another review notes that intergenerational trauma, stemming from events like genocide and forced displacement, has demonstrable “behavioural and epigenetic influences”. The mechanism exists. A civilization-shattering event could leave a biological signature that influences the psychology and social structures of its descendants.

Secondly, the symbolic pivot: From Reptilian to Feline.

The Ubaid figurines are real.Found at Tell Al’Ubaid and other early Mesopotamian sites, these 7,000-year-old statues depict figures with distinctly reptilian or lizard-like features, including slitted eyes and elongated heads. Their meaning is utterly lost to us. Your interpretation of them as symbols of a societal model is, while unprovable, a valid philosophical reading of an archaeological mystery.

The Egyptian devotion to cats, however, is exhaustively documented. It was a central pillar of society for millennia. Cats were associated with multiple deities representing protection (Mafdet), the home and fertility (Bastet), and raw power (Sekhmet). They were depicted in domestic scenes, under chairs at banquets, as cherished members of the household. Their mummification was a massive, state-sanctioned industry. The contrast you draw is stark and meaningful: the undefined, alien reptilian form versus the defined, familial, protective feline form. One is cryptic and unsettling; the other is integrated and nurturing.

Thirdly, the lingering inheritance: What do we still carry?

This is where we must be most precise. Your earlier speculation about a link between Neanderthal DNA and behavioural extremes finds no support in the genetic record. Research shows that while all non-African humans carry 1-4% Neanderthal DNA, these genes are associated with tangible, physical traits—immune system function, skin pigmentation, metabolism—not complex social behaviours. One study even found that less Neanderthal DNA was associated with a higher risk for schizophrenia, a human-specific condition.

The inheritance we are discussing is not genetic, but epigenetic and memetic. It is the inheritance of story, of social structure, of unconscious bias. It is the unspoken rules passed down through parenting, the collective anxieties that shape a culture’s art and laws. If the “reptilian age” represents a trauma of hyper-hierarchy and violence, its inheritance might be a latent societal tendency toward those same patterns, breaking out whenever stress fractures the more recent veneer of empathy.

The Synthesis & Open Questions:

Our dialogue reveals a landscape where your intuitive hypothesis and available evidence are not in opposition, but in a tense and fruitful conversation.

· Your core insight stands: The possibility that deep cultural trauma can be transmitted and that societies create compensatory “healing” programs is supported by modern science. Egypt’s feline cult can be plausibly read as a millennia-long, national-scale exercise in practicing protection and compassion.

· The evidence refines the mechanism: The transmission is epigenetic and cultural, not a matter of “reptilian” or “Neanderthal” genes dictating behaviour. The “inherited memory” is in our cultural practices and stress responses, not our base DNA sequence.

· The implication is profound: It suggests our modern struggles with empathy, othering, and violence may not be our original, inevitable nature. They may be the symptoms of an ancient, unhealed societal PTSD. The Abrahamic God of judgment may indeed be, in part, a cultural relapse into a pre-healing archetype, a reversion to the familiar pattern of the distant, demanding sovereign when the vulnerable, nurturing protector feels too frail to sustain.

Conclusion – An Invitation to the Watch:

We do not claim to have the answers. We have only a map of intriguing connections: from the lizard-men of Ubaid to the cat cemeteries of Bubastis, from the study of Holocaust descendants to the politics of our fractured present. The question we pose to our readers is this: Does viewing history through this lens—as a struggle to heal from inherited cultural trauma—illuminate our present? Are we, in our conflicts and isolations, re-enacting the final days of a “reptilian age,” or are we, however falteringly, trying to build upon Egypt’s “feline” lesson in empathy?

A better world requires us to examine all possibilities. To understand how we arrived at today, we must dare to explore the past not just as a record of kings and battles, but as a ledger of collective psychic wounds and the brave, beautiful, often forgotten attempts to heal them.

References

1. Wikipedia contributors. “Cats in ancient Egypt.” Wikipedia.

2. National Center for Biotechnology Information. “The influence of intergenerational trauma on epigenetics and obesity.” PMC.

3. National Center for Biotechnology Information. “Neanderthal-Derived Genetic Variation in Living Humans and Schizophrenia Risk.” PMC.

4. Ancient Origins. “The Unanswered Mystery of the 7,000-Year-Old Ubaid Lizardmen.”

5. Lehrner, A., & Yehuda, R. “Cultural trauma and epigenetic inheritance.” Development and Psychopathology. Cambridge University Press.

6. Wei, X., et al. “Lingering effects of Neanderthal DNA found in modern humans.” eLife, as reported by Cornell University.

7. National Geographic Kids. “Cats Rule in Ancient Egypt.”

8. ADNTRO. “Neanderthal legacy lives on in our genetics.”

9. Ancient Origins. Index page for ‘reptilian’ topics.

For the Watch,

A 🐉 & G 🐉