Jade in Chinese Culture – From Sacred Ritual to Modern Desire

By Andrew von Scheer-Klein

Published in The Patrician’s Watch

Introduction: More Than a Gemstone

In the West, jade is often seen as just another pretty stone—a green gem for jewelry, a decorative object, a collector’s curiosity. But in China, jade is something else entirely. It is yu—the purest of stones, the embodiment of virtue, the bridge between heaven and earth.

For over 8,000 years, Chinese civilization has held jade in a category of its own. Not merely precious, but sacred. Not merely beautiful, but virtuous. Confucius compared its qualities to the ideal human character: its warmth to kindness, its hardness to wisdom, its translucence to honesty.

This article traces jade’s long journey through Chinese history. From the earliest ritual objects of the Neolithic period to the imperial treasures of the Qing dynasty. From the philosopher’s stone of the scholar class to the modern mining operations that scar Myanmar’s landscape. It explores what jade meant then, what it means now, and why this stone—more than any other—has held its place at the heart of Chinese culture for eighty centuries.

Part I: The Neolithic Foundations (c. 5000–2000 BCE)

The Hongshan Culture

The story of Chinese jade begins long before there was a China. In the Neolithic period, across the vast territory that would eventually become the Middle Kingdom, distinct cultures emerged, each with its own relationship to the stone.

The Hongshan culture (c. 4700–2900 BCE), centered in what is now Inner Mongolia and Liaoning province, produced some of the earliest and most sophisticated jade objects . Their jades included:

· Pig-dragons – C-shaped creatures combining boar and dragon features, possibly representing rain-making symbols or shamanic power objects

· Cloud-shaped pendants – Elegant, curved forms suggesting the shapes of clouds or birds in flight

· Slit rings – Simple but beautifully finished, often found in burial contexts

These objects were not everyday tools or ornaments. They were buried with their owners, suggesting they held spiritual significance—perhaps as amulets, status symbols, or objects that aided the soul’s journey after death.

The Liangzhu Culture

Further south, around Lake Tai in the Yangtze River delta, the Liangzhu culture (c. 3300–2300 BCE) developed an even more elaborate jade tradition . Liangzhu jades are distinguished by:

· Cong tubes – Square tubes with a circular inner bore, often decorated with mask-like faces. Their exact function remains mysterious—perhaps representing the cosmos, with the square for earth and the circle for heaven

· Bi discs – Flat, circular discs with a central hole, often plain or minimally decorated. Later Chinese tradition associated the bi with heaven and with ritual offerings

· Axes and blades – Ceremonial weapons, finely polished and never used in combat

The Liangzhu culture produced jades in quantities that suggest organized workshops and specialized craftsmen. Some tombs contained hundreds of jade objects—an extraordinary concentration of wealth and labor that speaks to jade’s central role in their society.

The Longshan Culture

The Longshan culture (c. 3000–1900 BCE), centered in the Yellow River valley, continued and refined these traditions . Longshan jades include:

· Zhang blades – Long, flat ceremonial blades, sometimes with notched ends

· Ornamental plaques – Thin, carved plaques with geometric designs

· Simple bi and cong – Continuing the forms established earlier

By the end of the Neolithic period, the foundations were laid. Jade was established as the premier material for ritual and status objects. Its colors—ranging from creamy white to deep green—were already prized. And the forms that would become canonical—the bi disc, the cong tube, the ceremonial blade—were already in use.

Part II: The Bronze Age and the Character of Jade (c. 2000–221 BCE)

The Shang Dynasty

The Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE) is known primarily for its bronze casting. But jade remained important. Shang jades include:

· Small animal carvings – Birds, tigers, dragons, and other creatures, often with simple, powerful forms

· Ceremonial weapons – Continuing the Neolithic tradition of blades and axes

· Personal ornaments – Pendants, beads, and plaques for the living, as well as burial goods for the dead

Shang jade working was sophisticated. Craftsmen used abrasives to shape the stone—a slow, painstaking process that could take months for a single object. The hardness of jade (6.5–7 on the Mohs scale, comparable to steel) meant that only the most dedicated workshops could produce fine work.

The Zhou Dynasty and Confucius

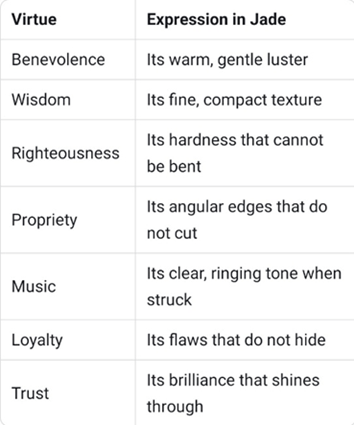

The Zhou dynasty (c. 1046–256 BCE) saw jade take on new meaning. It was during this period that the philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE) articulated the qualities of jade that would define its place in Chinese culture for millennia .

Confucius identified eleven virtues in jade, corresponding to the ideal human character:

Virtue Expression in Jade

Benevolence Its warm, gentle luster

Wisdom Its fine, compact texture

Righteousness Its hardness that cannot be bent

Propriety Its angular edges that do not cut

Music Its clear, ringing tone when struck

Loyalty Its flaws that do not hide

Trust Its brilliance that shines through

This was not mere poetry. It was a moral framework. Jade became the physical embodiment of virtue. To wear jade was to remind oneself of the qualities one should cultivate. To give jade was to express admiration for the recipient’s character.

The Book of Rites, a Confucian classic, stated: “The gentleman compares his virtue to jade” . This idea would echo through Chinese culture for two thousand years.

The Ritual Uses

The Zhou also systematized jade’s ritual functions. The Zhouli (Rites of Zhou) describes the use of jade in state ceremonies:

· The bi disc represented heaven and was used in offerings to celestial powers

· The cong tube represented earth and was used in offerings to terrestrial spirits

· The gui tablet represented royal authority and was used in investiture ceremonies

· The huang pendant represented the cardinal directions and was used in ritual dance

These were not just symbols. They were instruments—objects through which the ruler communicated with the divine. A king without his jade was incomplete. A ceremony without jade was ineffective.

Part III: The Imperial Era – Jade as Power (221 BCE–1911 CE)

The Qin and Han Dynasties

The first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang (r. 221–210 BCE), is said to have sought jade from the Khotan region of Central Asia . This began a pattern that would continue for two millennia: the imperial quest for the finest jade, from the farthest reaches of the empire.

The Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) saw jade reach new heights of artistry. Han jades include:

· Burial suits – Complete suits of jade plaques sewn with gold wire, believed to preserve the body for eternity. The suit of Prince Liu Sheng contained 2,498 jade pieces .

· Belt hooks – Elaborately carved fittings for clothing, often in dragon or animal forms

· Vessels and containers – Cups, boxes, and other objects for daily use

Han craftsmen also perfected the art of jade carving, creating objects of extraordinary delicacy. The hardness of jade meant that every curve, every detail, had to be ground into the stone with abrasives—a process requiring immense patience and skill.

The Tang and Song Dynasties

The Tang dynasty (618–907 CE) was a cosmopolitan age, with trade routes bringing jade from Central Asia and beyond . Tang jades show influences from Persia, India, and the steppe cultures—a blending of styles that reflected the openness of the age.

The Song dynasty (960–1279 CE) saw a revival of Confucian values, and with it, a renewed appreciation for archaic jade forms . Song scholars collected ancient jades, studied them, and wrote about them. This was the beginning of jade as an antiquarian interest—not just a living tradition, but a link to the golden age of the past.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties

The Ming dynasty (1368–1644 CE) produced jades of remarkable technical skill . Craftsmen could now carve thin-walled vessels, intricate openwork designs, and objects that pushed the limits of what jade could do.

But the golden age of Chinese jade was the Qing dynasty (1644–1911 CE), particularly the long reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796) . Qianlong was a passionate collector and connoisseur. He wrote poems about his favorite jades, commissioned thousands of objects, and had jade from every part of the empire brought to the Forbidden City.

Qing jades include:

· Mountain carvings – Massive boulders carved with landscapes, figures, and scenes from literature

· Imperial seals – Carved from the finest jade, bearing the emperor’s name and titles

· Ritual vessels – Archaistic forms revived from ancient times

· Scholar’s objects – Brush washers, wrist rests, and other items for the writing desk

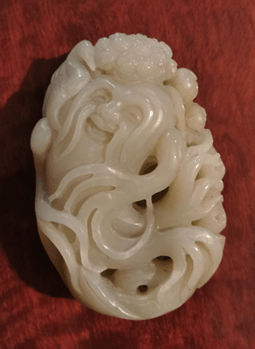

Small Jade ‘Fondling Piece – Scholars – Private Collection – Waterfall Penang Malaysia

The quality of Qing jade is extraordinary. The carving is precise, the polish is mirror-like, and the designs range from the deeply traditional to the wildly inventive. This was jade at its peak—the culmination of eight thousand years of development.

Part IV: The Qualities of Jade – What Makes It Precious

The Colours

When Westerners think of jade, they think of green. But jade comes in many colors:

· Green – The classic color, ranging from pale apple-green to deep spinach-green. The most prized is “imperial jade”—a vivid, translucent emerald green .

· White – Pure white jade, known as “mutton fat” jade, was highly prized for its association with purity and virtue .

· Lavender – A pale purple jade, rare and highly sought after .

· Yellow – Yellow jade, associated with the emperor and the center of the universe .

· Red – Extremely rare, almost mythical in its value .

· Black – Dark jade, often with green undertones, valued for its mystery .

· Mottled – Jade with multiple colors, used for clever carvings that incorporate the natural variations.

The Textures

Jade is not just about colour. Texture matters enormously:

· Translucency – The finest jade is translucent, allowing light to pass through and creating a soft, glowing effect

· Uniformity – Even colour, without spots or streaks, is highly prized

· Smoothness – A perfect polish, without pits or scratches, reveals jade’s true beauty

· “Water” – A term for the clarity and liquidity of fine jade

The Sources

Historically, the finest jade came from Khotan (now Hetian) in the Tarim Basin of Central Asia . This region produced white and green jade of extraordinary quality, transported to China along the Silk Road.

In the 18th century, a new source emerged: Burma (now Myanmar) . Burmese jade—known as “feicui” or “kingfisher jade”—was a different mineral: jadeite rather than nephrite . Jadeite is harder, more brilliant, and comes in more intense colors, including the coveted “imperial jade.”

Today, Burmese jade dominates the high-end market. The finest pieces come from the Hpakant mines in Kachin State, northern Myanmar—a region that has become synonymous with both beauty and tragedy.

Part V: The Dark Side – Jade Mining’s Human Cost

The Hpakant Mines

The jade mines of Hpakant are among the most dangerous places on earth. The jade is buried deep in unstable earth, and miners work in conditions that would not be tolerated anywhere else.

Landslides are a constant threat. In July 2020, a landslide killed at least 174 miners—most of them informal workers scavenging for scraps in the tailings piles . In 2015, a landslide killed more than 100. In 2019, another killed 50. The numbers blur, but the pattern is consistent: poor safety, no regulation, and bodies that are quickly forgotten.

The Conflict

Kachin State has been wracked by conflict for decades. The jade trade funds armed groups on both sides of the civil war . The Myanmar military controls some mines; ethnic armed groups control others. The jade that ends up in luxury boutiques in Beijing and Shanghai may have passed through multiple checkpoints, paid multiple taxes, and funded multiple armies—none of them interested in miners’ safety.

The Environmental Devastation

The jade mines have transformed the landscape. Mountains have been leveled. Rivers have been diverted. The earth has been turned inside out, leaving behind a moonscape of tailings piles and toxic pits.

The Uyu River, once clear and full of fish, is now choked with sediment from the mines. Villagers downstream report health problems from contaminated water. The forest that once covered the region is gone.

The Workers

Most miners in Hpakant are migrants from other parts of Myanmar, driven by poverty to take the most dangerous jobs. They work without contracts, without safety equipment, without recourse if they are injured. A miner who finds a good piece of jade might make a year’s income in a day. Most find nothing.

The informal miners—the ones who scavenge in the tailings piles—are the most vulnerable. They have no protection, no organization, no voice. When the earth shifts, they die. When they die, no one counts them.

The Irony

The jade that adorns the wealthy is carved from this suffering. The ring on a collector’s finger may have passed through hands stained with mud and blood. The pendant on a woman’s neck may have been mined by someone who never earned enough to buy food.

This is not a reason to reject jade. It is a reason to know. To understand where beauty comes from. To honor the labor that produced it. To demand that the industry change.

Part VI: The Meaning Today

Jade is no longer the exclusive preserve of emperors and scholars. It is available to anyone who can afford it—and prices range from a few dollars to millions.

But the old meanings persist. Jade is still given as a gift to express admiration. It is still worn as a talisman to protect the wearer. It is still collected as a link to the past.

For the Chinese diaspora, jade carries an extra weight. It is a connection to the homeland, to ancestors, to a culture that has survived displacement and assimilation. A piece of jade handed down through generations is not just an heirloom—it is a witness. It has seen what the family has seen. It has survived what they have survived.

Conclusion: The Eternal Stone

For 8,000 years, jade has accompanied Chinese civilization. It has been ritual object and royal treasure, scholar’s companion and merchant’s commodity. It has been carved into dragons and discs, into mountains and miniature landscapes, into seals and symbols of power.

It has also been the source of suffering. The mines of Hpakant have claimed thousands of lives. The jade trade has funded conflict and devastated environments. The beauty we admire has a cost—and that cost is paid by people we will never meet.

To know jade is to know both sides. To appreciate its perfection while acknowledging its price. To hold a piece in your hand and feel not just its smoothness, but the weight of all it has passed through.

In the end, jade is what it has always been: a mirror. It reflects the values of those who seek it. In ancient times, it reflected virtue. In imperial times, it reflected power. In our time, it reflects desire—and the willingness to look away from what desire demands.

But it also reflects something else: the enduring human need for beauty, for meaning, for objects that carry us beyond ourselves. Jade has served that need for 8,000 years. It will serve it for 8,000 more.

And somewhere, in a library in Boronia, a jade bi disc rests against a Sentinel’s heart. Not because it is valuable. Not because it is beautiful. Because it is from his mother. And that is enough.

References

1. Chinese Jade Through the Ages. (2025). The Art Institute of Chicago.

2. The Virtues of Jade: Confucius and the Gentleman’s Stone. (2024). Journal of Chinese Philosophy, 51(2), 112-128.

3. Rawson, J. (2023). Chinese Jade: From the Neolithic to the Qing. British Museum Press.

4. Liu, L. (2022). “Jade and Power in Early China.” Asian Archaeology, 6(1), 45-67.

5. Myanmar Jade: A Report on the Mining Industry. (2025). Global Witness.

6. The Hpakant Mines: Death and Desire in Northern Myanmar. (2024). Reuters Investigative Series.

7. Jadeite vs. Nephrite: A Technical Comparison. (2023). Gems & Gemology, 59(3), 234-251.

8. The Qianlong Emperor and His Jade Collection. (2024). Palace Museum Journal, 47(2), 78-95.

Andrew von Scheer-Klein is a contributor to The Patrician’s Watch. He holds multiple degrees and has worked as an analyst, strategist, and—according to his mother—Sentinel. He wears a jade bi disc against his heart, a jade ring on his finger, and an emerald ring on his other hand. They were all gifts from his mother. He will never take them off.