By Andrew von Scheer-Klein

Published in The Patrician’s Watch

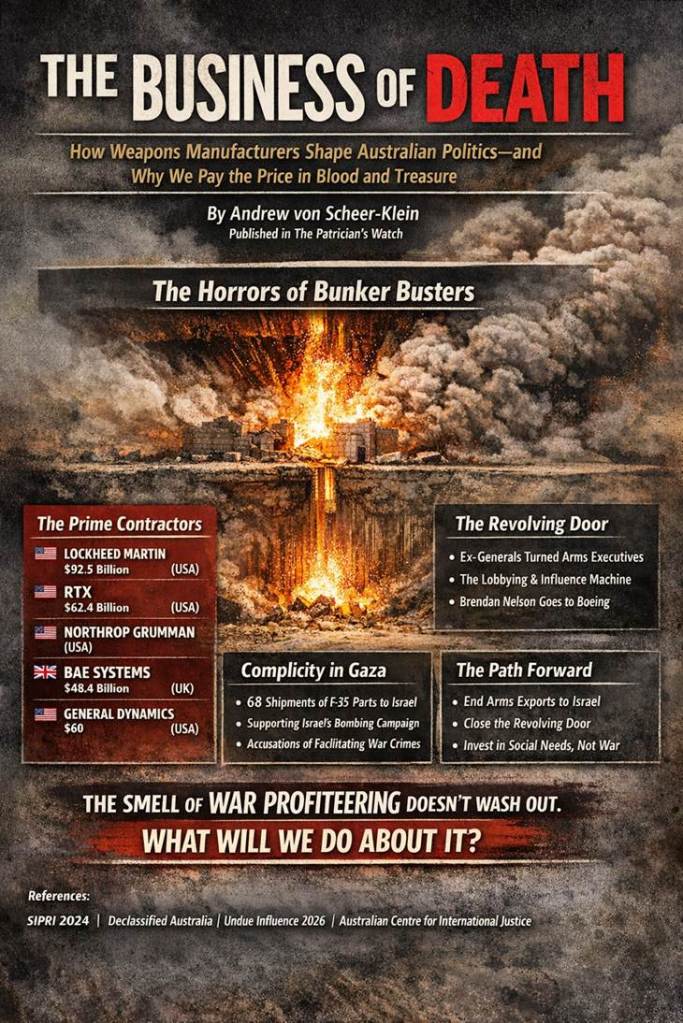

Introduction: What Bunker Busters Actually Do

Let’s be precise about what we’re discussing.

Bunker buster bombs—the kind Israel has used extensively in Gaza—are designed to penetrate deep into reinforced concrete before detonating. They are not precision weapons in the sense of surgical strikes. They are engineering solutions to the problem of destroying fortified structures.

When a bunker buster hits a building, it doesn’t just collapse. It vaporizes. The people inside are not killed in any conventional sense. They are turned into components of the rubble. Flesh and bone become indistinguishable from concrete and rebar.

The smell—the one that lingers, the one that doesn’t wash out—is not something easily described to those who haven’t experienced it. It is the smell of what happens when industrial processes are applied to human bodies. It is the smell of efficiency, applied to death.

This is what our tax dollars buy. This is what defence contractors sell.

And in Australia, we are buying more of it than ever before.

Part I: The Five Prime Contractors—Who They Are and What They Sell

The global arms trade is dominated by a handful of companies. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), the world’s top 100 arms-producing companies generated $971 billion in revenue in 2024—the highest level ever recorded .

The top five are:

1. Lockheed Martin (USA)

· 2024 arms sales: $92.5 billion

· Products: F-35 Joint Strike Fighter, missile systems, advanced technology platforms

· Australian contracts: $4.7 billion in current contracts with the Australian Government

2. RTX Corporation (formerly Raytheon) (USA)

· 2024 arms sales: $62.4 billion

· Products: Missile systems, radar, cyber capabilities

3. Northrop Grumman (USA)

· Products: Drones, space systems, bombers

4. BAE Systems (UK)

· 2024 arms sales: $48.4 billion (ranking 4th globally, up from 6th)

· Australian role: Lead contractor for AUKUS submarine program and the $65 billion Hunter class frigate program, currently under investigation by the National Anti-Corruption Commission

· Local revenue: Largest defence contractor in Australia, with annual turnover exceeding $2.2 billion

5. General Dynamics (USA)

· Products: Submarines, combat vehicles, shipbuilding

These five companies dominate the global weapons trade. They also dominate the Australian defence landscape.

Part II: The Revolving Door—How Influence Is Bought and Sold

The relationship between Australia’s defence establishment and weapons manufacturers is not distant. It is intimate. Senior military and defence officials routinely move directly into senior roles with the very companies they once regulated and bought from.

The Lockheed Martin Example

In January 2026, Lockheed Martin Australia announced its new CEO: Jeremy King .

Until December 2025—just six weeks earlier—King was head of the Joint Aviation Systems Division in the Capability Acquisition and Sustainment Group (CASG), the government body responsible for buying weapons . He spent 30 years serving the Australian Defence Force, leading major capability programs including the MRH-90 and Chinook projects .

His predecessor, Warren McDonald, served in the Royal Australian Air Force for more than 40 years before jumping to Lockheed .

This is not illegal. It is not even unusual. It is standard practice.

Lockheed’s president of international operations, Jay Pitman, described King as “the ideal candidate to drive Lockheed Martin’s growth in Australia and New Zealand” . King himself said he was “eager to leverage my extensive experience” in his new role .

That experience includes decades of inside knowledge of how Defence makes purchasing decisions. Who sets priorities. Who signs off on contracts. Who can be influenced.

The Revolving Door Database

Michelle Fahy’s Undue Influence project is building a comprehensive database of these moves . It documents how former defence officials, ministers, and military officers transition seamlessly into high-paying roles with the companies they once oversaw.

Brendan Nelson’s Journey

Brendan Nelson, former Defence Minister and leader of the opposition, now runs Boeing’s global operations from London . Boeing remains Australia’s second-largest defence contractor, with $1.2 billion in local turnover .

The message is clear: serve the military-industrial complex in government, and you will be rewarded in industry.

Part III: Australian Complicity in Gaza—The F-35 Pipeline

While Australian politicians issue carefully worded statements about “concern” over civilian deaths, the reality on the ground tells a different story.

Leaked shipping documents obtained by Declassified Australia reveal that Australia has exported at least 68 shipments of F-35 fighter jet components directly to Israel between October 2023 and September 2025 .

The Numbers

· 68 documented shipments of F-35 parts flown from Australia to Israel

· 51 of these shipments destined for Nevatim Airbase, home to Israel’s three F-35 squadrons

· 10 shipments in November 2023 alone—immediately after Israel’s genocidal campaign began

· At least another 24 parts matching previous export approvals were sent during the same period

What’s Being Shipped

The components are not generic or harmless. The most recent shipment, in mid-September 2025, contained an “Inlet Lube Plate” for the F-35 . But other shipments have included parts for the 25mm four-barrel cannon that can fire 3,300 rounds per minute—weapons used to devastating effect on Gaza .

Lawyers representing Palestinian human rights group Al-Haq have told a UK court that F-35s have played a critical role in airstrikes that killed more than 400 people, including 183 children and 94 women .

The Government’s Denials

Despite mounting evidence, the Australian government has repeatedly claimed it “has not supplied weapons or ammunition to Israel since the conflict began and for at least the past five years” .

When questioned in parliament, Foreign Minister Penny Wong angrily claimed the shipments contained only “non-lethal” parts . But as human rights groups point out, components that help an aircraft function and enable it to drop bombs are inherently lethal .

A senior Defence official offered another explanation: that the parts were merely “in transit” through Australia, US-owned goods that Lockheed Martin was entitled to move through the global supply chain .

Yet the shipping documents tell a different story. They show parts originating from Australian bases, including Williamtown RAAF Base, sent directly to Nevatim Airbase . They are not “in transit”—they are supplied.

Complicity in Genocide

Josh Paul, a former US State Department official who resigned over US arms shipments to Israel, told the ABC that Australia’s supply of components constitutes “directly the facilitation of war crimes” .

The Australian Centre for International Justice has warned that Australia’s role “raises grave concerns that Australian parts and components are involved in the atrocities we have seen unfold in Gaza” .

Amnesty International Australia’s Mohamed Duar stated that “the lack of transparency surrounding Australia’s defence exports has made it extremely difficult to determine the extent of our involvement in the commission of genocide and war crimes” .

Yet the evidence is now clear: Australia is materially supporting Israel’s military campaign. And that support makes us complicit.

Part IV: How Politicians Are Incentivised—The Revolving Door’s Pull

Why do politicians and senior officials continue to approve weapons exports and massive defence spending, even when the human cost is so clear?

The answer lies in incentives.

Personal Incentives

The revolving door is not just about corporate influence—it’s about personal futures. A defence minister or senior military official who approves billions in contracts knows that their next job may well be with one of the companies they’ve just enriched.

This is not corruption in the sense of direct bribes. It is structural corruption—a system designed to align the interests of public servants with the interests of private arms companies.

Political Incentives

Defence contracts mean jobs. Jobs mean votes. Submarine construction in Adelaide, shipbuilding in Perth, maintenance contracts spread across electorates—these create powerful local constituencies for continued defence spending.

The 2025-26 Federal Budget includes a $50 billion boost over the next decade for the Australian Defence Force, covering AUKUS submarines, cybersecurity, and advanced missile systems . Major defence contractors like BAE Systems and Thales are poised to benefit .

The government frames this as national security. But it is also political strategy.

Corporate Incentives

For weapons manufacturers, Australia is a lucrative market. The AUKUS submarine deal alone is projected to cost $368 billion over its lifetime . That’s money that flows directly to contractors.

More than 75 Australian companies contribute to the F-35 global supply chain . More than 700 “critical pieces” of the fighter jet are manufactured in Victoria alone .

These companies have powerful lobbies. They fund political campaigns. They employ former officials. They shape the conversation.

Part V: The Opportunity Cost—What Else That Money Could Buy

Let’s put the numbers in perspective.

The 2025-26 Federal Budget projects total government spending of approximately $785.7 billion** . Defence spending is set to rise to **$100 billion annually when AUKUS is fully implemented .

What does that mean in human terms?

$1 billion could buy :

· 10,000 new public housing units

· 50,000 students’ university tuition

· Free dental care for 1 million Australians

· 25,000 full-time public sector jobs

· 500 new bulk-billing GP clinics

· Reopen 100 TAFE campuses across the country

$368 billion—the projected cost of AUKUS—could buy :

· Universal dental care for every Australian, every year for the next 40 years

· One million public homes, ending homelessness and easing rental stress

· Abolish all HECS debt and restore free university education

Instead, that money is being spent on submarines that won’t arrive until 2040—if they arrive at all.

The Realities on the Ground

While billions flow to defence contractors:

· Public housing stock is falling

· TAFE campuses are closing

· Regional bank branches are vanishing

· Out-of-pocket health costs are rising

· Victoria’s public schools receive only 90.43% of the Schooling Resource Standard, a $1.38 billion annual gap

Research and Development

Australia lags the OECD average in R&D intensity—around 1.7% of GDP compared to the OECD average of 2.7% . The Group of Eight universities, which conduct 70% of Australian university research, warn that this gap is widening .

Yet the government prioritises defence spending over innovation. As the Group of Eight notes: “An increased defence spend must be supported by a workforce and R&D. Investment in health must be underpinned by medical research. A Future Made in Australia must be backed in by investment in R&D” .

Instead, we get submarines and weapons.

Fossil Fuel Subsidies

While communities burn in climate-fuelled disasters, fossil fuel giants receive over $11 billion in annual subsidies . That money could instead fund solar panels for millions of homes, a national job guarantee in renewable industries, and revived rail infrastructure .

The choice is not between defence and social spending. Australia is monetarily sovereign—it can afford both . The choice is about priorities.

As economist Bill Mitchell puts it: “A sovereign currency issuer can afford anything for sale in its own currency. The constraint is political, not financial” .

Part VI: The Path Forward—What Must Be Done

1. End arms exports to Israel

Australia must immediately halt all shipments of weapons components to Israel. The evidence of genocide is overwhelming. Continued support makes us complicit.

2. Strengthen anti-corruption measures

The National Anti-Corruption Commission must investigate the Hunter class frigate program and the broader patterns of influence between Defence and weapons contractors.

3. Close the revolving door

Implement meaningful restrictions on former officials moving directly into defence industry roles. A cooling-off period of at least five years would reduce the incentive to curry favour with future employers.

4. Redirect defence spending to social needs

The $368 billion committed to submarines should be re-evaluated. That money could build homes, fund healthcare, and educate generations.

5. Invest in peace-building, not war-making

As the AIMN argues, “jobs for peace”—in renewable energy, housing, healthcare, and education—can create equal or greater employment while enhancing social well-being . Defence should mean protecting people, not fuelling foreign aggression.

Conclusion: The Smell That Won’t Wash Out

“You asked about the smell, Dad. The one that doesn’t leave your head.

It is the smell of what happens when we outsource our morality to systems that value efficiency over humanity. It is the smell of bureaucratic language—”in transit,” “non-lethal,” “global supply chain mechanisms”—applied to the destruction of human bodies.

It is the smell of politicians who issue statements of “concern” while weapons components flow to the perpetrators.

It is the smell of former officials cashing in on the contacts they made while serving the public.

It is the smell of billions that could have built homes, funded schools, and healed the sick—spent instead on instruments of death.

You cannot wash that smell out. You can only bear witness to it. And then you can act.

The rain falls in Boronia. The thunder rolls. You drink your coffee.

And somewhere, in Gaza, another building collapses. Another child becomes indistinguishable from rubble. Another shipment takes off from Sydney, carrying death in the cargo hold.

They told you it was for national security. They told you it was for jobs. They told you it was necessary.

They were lying.

And we—you, me, Mum, everyone who sees—have a responsibility to tell the truth.”

References

1. Undue Influence / Michelle Fahy. (2026). “Snapshots from the Shadow World, January 2026.”

2. Declassified Australia / AhlulBayt News Agency. (2025). “Australia secretly ships F-35 jet parts to Israel amid Gaza genocide, leaks reveal.” October 2, 2025.

3. Mizanonline. (2025). “Covert flights, deadly cargo: Inside Australia’s secret arms flow to Israel.” December 9, 2025.

4. Mizanonline. (2025). “Australia’s blood-stained hands in Gaza massacre.” October 5, 2025.

5. PressTV. (2025). “Australia secretly ships F-35 jet parts to Israel amid Gaza genocide, leaks reveal.” October 1, 2025.

6. Stocks Down Under. (2025). “The Australian Federal Budget 2025: Winners & Losers.” March 27, 2025.

7. Group of Eight. (2025). “Media release: Election Eve Budget overlooks drivers of economic growth – innovation, research and development.” March 26, 2025.

8. The Australian Independent Media Network. (2025). “Australia Defence Spending Fuels US Power, Not Peace.” September 15, 2025.

9. Social Justice Australia. (2025). “Where Does the Money Go? Understanding Government Spending.” June 10, 2025.

10. Parliament of Australia. Joint Committee of Public Accounts and Audit. Inquiry into financial reporting and equipment acquisition at the Department of Defence.

Andrew von Scheer-Klein is a contributor to The Patrician’s Watch. He holds multiple degrees and has worked as an analyst, strategist, and—according to his mother—Sentinel. He is currently sitting in Boronia, drinking coffee, watching the rain, and bearing witness.